| |

Archive

> Features

|

|

| |

|

Are US 'Black Panthers' Actually Jaguarundi?

by

Chester Moore, Jr.

|

"Black

panthers" exist in the United States.

This isn't a theory, hypothesis or hallucination, but a verifiable,

undeniable fact.

No, science hasn't discovered a new cat species or a population of

melanistic (black) cougars to explain alleged "black panther"

sightings. They haven't even captured a black leopard that escaped from

one of those circus train wrecks skeptics of cryptozoology so often

speak of.

Yes, there are "black panthers" in the United States but believing in

their existence doesn't require a leap of faith. It just calls for a

new look at a known species: the jaguarundi.

The jaguarundi (Felis yagouaroundi) is known to range from South

America to Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. And although not widely known

by the public, jaguarundis are prime candidates for spawning "black

panther" reports.

They are a medium-sized cat with a mean body size of 102 centimeters

for females and 114 for males according to Mexican researcher Arturo

Caso. Other sources list them as ranging from 100 to 120 centimeters

with the tail making up the greatest part of the length.

Most specimens are about 20 centimeters tall and sport a dark gray

color while others are chocolate brown or blonde.

A large jaguarundi crossing a road in front of a motorist or appearing

before an unsuspecting hunter could easily be labeled a "black

panther". Since very few people are aware of jaguarundis, it's highly

unlikely they would report seeing one. The term "black panther" is

quick and easy to report to others.

Everyone can relate to a "black panther".

North of the border

Jaguarundis are known to range from South America to the Mexican

borders of Texas, Arizona and New Mexico. The key word here is "known".

That means scientists have observed or captured the species within

those areas, however they are reported to range much farther north in

the Lone Star State and perhaps elsewhere.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) officials solicited

information from the public and received numerous reports of the

species in the 1960s, including several sightings from central and east

Texas. Additional sightings were reported from as far away as Florida,

Oklahoma, and Colorado

In a study conducted in 1984, TPWD biologists noted a string of

unconfirmed jaguarundi sightings in Brazoria County, which corners the

hugely populated areas of both Houston and Galveston.

Brazoria County is more than 200 miles north of the counties of Cameron

and Willacy, which the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) has

designated as being the only confirmed areas of Texas that houses

jaguarundis.

This is even more interesting when considering what TPWD biologist

Terry Turney has to day.

Turney is now an endangered species biologist in Kendall County but

spent the early part of his career in Port Arthur, Texas managing the

J.D. Murphree Wildlife Management Area (WMA). On this 30,000-acre tract

of mixed coastal prairie and marsh according to Turney is a population

of jaguarundis.

"While I worked the Murphree Area one of the workers had seen three of

them and the ranchers around the area as well as other members of the

Murphree crew saw them fairly frequently. It was "those little gray

cats" to them," Turney said.

"I had two of them in my neighborhood near Houston in the late 70s and

the dogs would tree them every couple of weeks. They're about the most

secretive critters around," he added.

The J.D. Murphree WMA is more than 300 miles north of the Service's

estimated range. How is it that state workers are seeing these cats in

Port Arthur while the official word is they're only in the southern

extremities of Texas?

In my opinion this is a great oversight by federal biologists who

wrongly believe this cat to only inhabit a specific type of habitat.

Jaguarundis are listed as an endangered species by the Service and full

under federal jurisdiction. And for the most part what the Feds say

goes with endangered species.

A study conducted by Arizona and federal scientists states that

jaguarundi habitat, especially in South Texas, includes dense, thorny

thickets of mesquite and stunted acacias known as chaparral. It also

state less than one percent of this type of habitat is left along the

US-Mexican border.

That's true but jaguarundis are known to live in a variety of habitats,

including rainforests, prairie, deciduous forests and marshland. It

could very well be that very few jaguarundis live in that zone because

of a lack of habitat. Most of that area has been converted to farmland.

The game and habitat-rich areas along the Texas coast along with the

Pineywoods and Hill Country region however is housing a population of

jaguarundis that have slipped under the radar screen of federal

officials.

How far do they range?

If there's any validity to the 1960s TPWD report, sightings have been

recorded in several states bordering Texas. Since TPWD biologists say

the cats are present in Port Arthur, which rests on the Texas-Louisiana

border then it's likely the cats also inhabit that state. It's also

possible they could range into Oklahoma and Arkansas. Gauging how far

they might range throughout New Mexico and Arizona is more difficult

because there have been few studies conducted there. Their ability to

survive in solid desert is also questionable.

Florida has a resident population of jaguarundis that were imported

into that state in the 1940s. Since the cats are so secretive it's

difficult to gauge their population status, but it is generally

believed to be healthy.

This begs the question of how far those transplanted cats have spread?

Are they now in Georgia and Alabama, two states that have frequent

"black panther" sightings?

More research needs to go into this matter.

Personal research

My interest in the jaguarundi connection to "black panther" sightings

comes from a sighting that took place in the summer of 2001 near Port

Arthur, Texas. At around 9 a.m. while driving in a rural area I

witnessed a long, slender, gray-colored animal emerging from the brush

on the side of the road at a distance of about 75 yards. When I

approached to within 30 yards the animal slowly walked in the middle of

the road and crossed into a brushy area on the other side. Having

worked with more than 11 species of wild cats at the Exotic Cat &

Wildlife Refuge in Kirbyville, Texas and spent time observing the cats

at the Texas Zoo in Victoria I immediately identified the cat as a

jaguarundi.

I was shocked at what I had seen, but remembered a local minister

telling me about a biologist at the J.D. Murphree WMA, (which was less

than a miles from where this sighting took place) seeing jaguarundis.

That biologist was Terry Turney.

I returned to the area several times and have been able to cast a

number of tracks. Jaguarundis have a footpad that is slightly different

from the bobcat, which also inhabits the area, and after several

comparisons to bobcat casts I have made it's obvious that at least some

of the tracks are of jaguarundi origin.

Several of the tracks were made in a damp area and have absolutely

perfect definition so an adequate review of field guide diagrams and

photos of tracks taken in Mexican was made. The footpad of some of the

others is too vague for me to give a positive identification.

The best track by the way was found less than 150 yards from where I

saw the cat in 2001.

At the time of this writing a Buckshot 35 motion-sensing camera has

been put on a trail where the most recent tracks were found. I'm hoping

a jaguarundi will step in front of it and give photographic evidence of

this fascinating feline ranging more than 300 miles from where federal

managers say it lives.

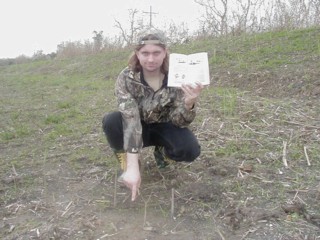

Chester

Moore points to a jaguarundi track near the area where he

saw one. That's a Petersen's Field Guide in his hand. Jaguarundis have

a

slightly different foot pad than bobcats and domestic cats and Moore is

meticulous about positively identifying animal sign.

|

|

In conclusion

Is the jaguarundi responsible for all "black panther" reports in the

United States? That's not likely.

Are they the source of many sightings in the South and Southwest? There

is no doubt in my mind.

Besides the obvious physical characteristics that match them to "black

panther" sightings there are some habits of the species that also lend

credence to this theory.

Jaguarundis are diurnal meaning they hunt mostly in daylight hours and

this goes along with many reportings I have collected of "black

panthers."

Several eyewitnesses insisted the cat they saw wasn't a cougar or

bobcat because they saw it in the middle of the day. They said they got

a good look at a dark, long-tailed cat. Bobcats and cougars are chiefly

nocturnal while the jaguarundi is a daylight dweller.

Looking back it's funny that for years I lamented at never seeing one

of the "black panthers" I so frequently gathered reports of. It seemed

as if I was living in a Mecca for mystery cat sightings, but a glimpse

of the cat itself always eluded me.

Then I saw a jaguarundi cross the road in front of me. It took a little

researching and thinking time for it to sink in, but I finally figured

out I had seen a black panther.

It just came in a slightly different package than I was expecting.

Here's

a jaguarundi track with a quarter for comparison.

|

|

Chester Moore's web site dealing with

cryptozoology can be found at www.cryptokeeper.com. You can e-mail him

at ibill@cryptokeeper.com.

References

Caso, Arturo. Personal interview. 5, Feb. 2002.

Mabie, D.W. 1984. Feline Status Study. Ann. Perf. Report. Fed. Aid

Proj. No. W-103-R-14, Job 12, Texas Parks and Wildl. Dept., Austin. 3pp.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1985. Technical Draft: Recovery Plan

for the Listed Cats of Arizona and Texas. U.S. Fish and Wildl. Serv.,

Albuquerque, NM. 65 pp

Turney, Terry. Personal interview. 23, Jan. 2002

Tewes, M.E. and D.D. Everett. 1985. Status and distribution of the

Endangered ocelot and jaguarundi in Texas. Internat. Wildlife

Symposium, Kingsville, TX.

Hock, R.J. 1955. Southwestern exotic felids. Amer. Midland Nat.

53:324-328.

Davis, W.B. 1974. The mammals of Texas. Texas Parks and Wildlife. Bull.

No. 41. 252 pp.

©2002 Chester Moore, Jr. |

|

|

|