| |

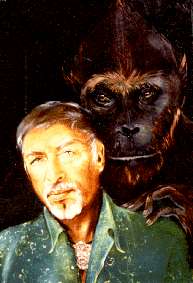

Bernard Heuvelmans (1916

- 2001)

Illustration by

Alika Lindbergh

An appreciation

of a friend by Loren

Coleman

Switzerland's Museum of Zoology of Lausanne informed

cryptozoologists worldwide on the morning of 24 August 2001, of the

death of Dr. Bernard Heuvelmans, 84, the "Father of

Cryptozoology." Around noon on August 22nd, without suffering,

Heuvelmans, passed away, in his bed at his Le Vesinet, France home,

with his faithful dog nearby.

Heuvelmans, who had become a Buddhist during his lifetime, was

buried in Buddhist monk attire during a private funeral at Le

Vesinet on August 27. His former wife, colleague, artist

collaborator Alika (Monique Watteau) Lindbergh, who cared for him in

his declining years, was in charge of the ceremony, following his last

wishes.

Heuvelmans' death is sad news. His towering presence in the

field leaves a long shadow. His influence is

great. Heuvelmans' contributions to cryptozoology, zoology, and

anthropology are significant and far-reaching, and his impact on

generations to come will cross decades.

Bernard Heuvelmans was born in Le Havre on October 10, 1916, of a

Dutch mother and a Belgian father in exile, and was raised as a

"native of Belgium." Heuvelmans found he had a love of natural

history from an early age, keeping all kinds of animals, especially

monkeys. At school, he shocked his Jesuit teachers by his unholy

interest in evolution and jazz. His interest in unknown animals was

first piqued as a youngster by his reading of science-fiction

adventures such as Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under

the Sea and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World. He

never forgot these initial passions.

Heuvelmans obtained his higher education at the University Libre of

Brussels. While at the university, he won the first prize for small

bands at an International Congress of Amateur Jazz. At the age of 23

years, before World War II, he obtained a doctor's title in

zoological sciences. His thesis was dedicated to the classification of

the hitherto unclassifiable teeth of the aardvark (Orycteropus

afer), a unique African mammal. Heuvelmans then spent the next

years writing about the history of science, publishing numerous

scientific works notably in the Bulletin of the Royal Museum of

Natural History of Belgium. His interests continued to extend beyond

the zoological realm. Captured by the Germans after he was called up

for military service from Belgium, he escaped four times before

eking out a living as a professional jazz singer and then as a

science writer. He saw himself as a humanist in the broadest sense,

and he published two works late in the war: The Man Among Stars

(1944) and The Man in the Hollow of the Atom (1943). The

Germans, during the war, arrested him because his writings offended

them, and then the Belgians arrested him afterwards, because he had

written them at all.

Settling in Paris and more particularly in Le Vésinet from

1947, Heuvelmans became a comedian, a jazz musician (From

Bamboula to Be-bop, 1949), and a writer (The Secret of Fates

in three volumes, The Continuation of the Life, The

Abolition of the Death, The Renovation, 1951-1952).

When Heuvelmans read a January 3, 1948 Saturday Evening Post

article ("There Could be Dinosaurs"), in which biologist Ivan T.

Sanderson sympathetically discussed the evidence for relict

dinosaurs, Heuvelmans decided to pursue his vague, unfocussed interest

in hidden animals in a systematic way. At the time, he

was translating numerous scientific works, among which was The

Secret World of the Animals by Dr. Maurice Burton, which was

republished afterward in seven volumes under the title Encyclopedia

of the Animal Kingdom.

Heuvelmans began to gather material about yet-to-be-discovered

animals in what he would later refer as his growing "dossiers" on

them. From 1948 on, Heuvelmans exhaustively sought evidence in

scientific and literary sources. Within five years he had amassed so

much material that he was ready to write a large book. That book turned

out to be Sur la piste des betes ignorees, published

in 1955, and better known in its English translation three years

later as On the Track of Unknown Animals. Almost five

decades later, the book remains in print, with more than one million

copies sold in various translations and editions, including one in

1995, with a large updated introduction.

The book's impact was enormous. As one critic remarked at the time,

"Because his research is based on rigorous dedication to scientific

method and scholarship and his solid background in zoology,

Heuvelmans's findings are respected throughout the scientific

community." Soon Heuvelmans was engaged in massive correspondence

as his library and other researches continued.

In the course of letter-writing, he invented the word

"cryptozoology" (it does not appear in On the Track).

That word saw print for the first time in 1959 when French

wildlife official Lucien Blancou dedicated a book to the "master of

cryptozoology."

Heuvelmans corresponded with many cryptozoologists worldwide, as he

did with me, over the decades. By the 1960s, most in the field had

elevated Blancou's phrase in honor of Heuvelmans, and Heuvelmans was

being called the "Father of Cryptozoology."

Writing in Cryptozoology in 1984, Heuvelmans said, "I tried

to write about it according to the rules of scientific

documentation." Because of the unorthodox nature of his interests,

however, he had no institutional sponsorship and had to support

himself with his writing. "That is why," he wrote, "I have always

had to make my books fascinating for the largest possible audience."

Heuvelmans and his book influenced the investigative work of

cryptozoology supporter Tom Slick. Sanderson, who influenced

Heuvelmans, in turn was influenced by Heuvelmans. Heuvelmans served

as a confidential consultant, along with such intellectual early

contributors like anthropologist George Agogino and zoologist Ivan

Sanderson, on Slick's secret board of advisors. Heuvelmans was asked

to examine the "Yeti skullcap" brought back by Sir Edumund Hillary's World

Book expedition of 1960. He was also one of the first to declare

it was a ritual object made from the skin of a serow, a small

goatlike animal found in the Himalayas, even before Hillary's

debunking of the yeti took place. Heuvelmans' extensive files on

the Slick expeditions remained mostly unpublished until he

contributed some for inclusion in the 1989 book, Tom Slick and

the Search for the Yeti.

On the Track of Unknown Animals was concerned

exclusively with

land animals. The second of Heuvelmans' landmark works to be

translated into English, In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents

(1968), covered the ocean's unknowns, including the recognized but

still in some ways enigmatic giant squid.

In 1968, Heuvelmans (at Sanderson's invitation) examined what was

represented to be the frozen cadaver of a hairy hominoid, the

subject of his L'homme de Neanderthal est toujours vivant

(with Boris Porshnev, 1974). Other books, none yet translated into

English, include works on surviving dinosaurs and relict hominids in

Africa.

Heuvelmans's Center for Cryptozoology, established in 1975, was

first housed near Le Bugue in the south of France, but in the 1990s,

moved to LeVesinet, closer to Paris. It consisted of his huge

private library and his massive files, his original treasured

dossiers. Heuvelmans was elected president when the International

Society of Cryptozoology was founded in Washington, D.C., in 1982.

He held that position until his death. He also was involved with the

British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club and other efforts for

active cryptid studies globally. The decades saw more and more

honors amassed, as for example, when in 1990, he was named a honorary

member of the Cryptozoology Association of Russia. In a 1984

interview Heuvelmans expressed the desire to write a 20-volume

cryptozoology encyclopedia, but owing to the death of a translator

and other problems with his publisher, no volume appeared before

Heuvelmans' death.

Down through the years, without fanfare, Heuvelmans journeyed from

the shores of Loch Ness to the jungles of Malaysia, from Africa to

Indonesia, interviewing witnesses and examining the evidence for

cryptids.He produced a few articles along the way, and infrequently

gave news interviews. But beginning in the 1990s, he would avoid media

events. For example, when a television network asked in 1994

and 1995, to tape an interview with Heuvelmans about the Minnesota

Iceman, he refused to come to America to do it, and then denied a

filming in France. Although he had had a French television

program on natural history mysteries some two decades earlier, he

routinely would not grant most mainstream interviews in the last

decade of his life.

He also hardly ever trekked to formal meetings. For many of us

in North America, visiting with him, for example, at an early 1980s

gathering in New York City, will now always be a delightful and rare

memory. When in February 1997, he was awarded the Gabriele

Peters Prize for Fantastic Science at the Zoological Museum of the

University of Hamburg, Germany, he was unable to appear to collect

the prize of 10,000 Marks (about $6000) and sent his friend,

journalist, and cryptozoologist Werner Reichenbach, to accept on his

behalf.

Heuvelmans's health began to more rapidly fail in the mid-1990s;

still he continued to work on completing his grand plan for his

multi-volume encyclopedia. In 1999, he donated his vast

holdings and archives in cryptozoology to The

Museum of Zoology of Lausanne in Switzerland, following

through on a commitment he had made in 1987. By 2001, many of us

were dismayed to find he was mostly bedridden, refusing visits, and

in very poor health.

In his waning years, his mind was filled with worries that no one

would credit him for what he had done. He need not have troubled

himself. Heuvelmans said he merely wanted to be remembered as "The

Father of Cryptozoology." He will be recalled thusly for his

efforts on behalf of the new science, as well as much more, for his

personality and scholarship. Bernard Heuvelmans, dead at 84, will

hardly be forgotten.

Nevertheless, Heuvelmans' friendship, fresh insights, and frisky

humor will be missed. Goodbye, my friend.

A list of Heuvelmans's books follows:

1955 Sur la piste des bêtes ignorées. Paris:

Plon.

1958 Dans le sillage des monstres marins - Le Kraken et le

Poulpe Colossal. Paris: Plon.

1958 On the Track of Unknown Animals. London:

Hart-Davis.

1959 On the Track of Unknown Animals. New York: Hill and Wang

1965 Le Grand-Serpent-de-Mer, le problème zoologique et

sa solution. Paris: Plon.

1965 On the Track of Unknown Animals. (Abridged, revised.)

New York: Hill and Wang.

1968 In the Wake of Sea Serpents. New York: Hill and Wang.

1975 Dans le sillage des monstres marins - Le Kraken et le

Poulpe Colossal. Paris: François Beauval : 2nd

édition revue et complétée.

1975 Le Grand-Serpent-de-Mer, le problème zoologique et

sa solution. Paris: Plon, 2nd édition revue et

complétée.

1978 Les derniers dragons d'Afrique. Paris: Plon.

1980 Les bêtes humaines d'Afrique. Paris: Plon.

1995 On the Track of Unknown Animals. London: Kegan

Paul International.

Heuvelmans, Bernard, and Boris F. Porchnev

1974 L'homme de Néanderthal est toujours vivant.

Paris, Plon.

_________________________

Obituary by Loren Coleman

http://www.lorencoleman.com

©2001

Loren Coleman

Permission to reproduce is granted if copyright notice is attached.

|

|